Cable theory

Classical cable theory uses mathematical models to calculate the flow of electric current (and accompanying voltage) along passive [1] neuronal fibers (neurites) particularly dendrites that receive synaptic inputs at different sites and times. Estimates are made by modeling dendrites and axons as cylinders composed of segments with capacitances  and resistances

and resistances  combined in parallel (See Figure 1). The capacitance of a neuronal fiber comes about because electrostatic forces are acting through the very thin phospholipid bilayer (See Figure 2). The resistances in series along the fiber

combined in parallel (See Figure 1). The capacitance of a neuronal fiber comes about because electrostatic forces are acting through the very thin phospholipid bilayer (See Figure 2). The resistances in series along the fiber  is due to the cytosol’s significant resistance to movement of electric charge.

is due to the cytosol’s significant resistance to movement of electric charge.

Contents |

History

Cable theory in computational neuroscience has roots leading back to the 1850s, when Professor William Thomson from panvel(later known as Lord Kelvin) began developing mathematical models of signal decay in submarine (underwater) telegraphic cables. The models resembled the partial differential equations used by Fourier to describe heat conduction in a wire.

The 1870s saw the first attempts by Hermann to model axonal electrotonus also by focusing on analogies with heat conduction. However it was Hoorweg who first discovered the analogies with Kelvin’s undersea cables in 1898 and then Hermann and Cremer who independently developed the cable theory for neuronal fibers in the early 20th century. Further mathematical theories of nerve fiber conduction based on cable theory were developed by Cole and Hodgkin (1920s-1930s), Offner et al. (1940), and Rushton (1951).

Experimental evidence for the importance of cable theory in modeling real nerve axons began surfacing in the 1930s from work done by Cole, Curtis, Hodgkin, Sir Bernard Katz, Rushton, Tasaki and others. Two key papers from this era are those of Davis and Lorente de No (1947) and Hodgkin and Rushton (1946).

The 1950s saw improvements in techniques for measuring the electric activity of individual neurons. Thus cable theory became important for analyzing data collected from intracellular microelectrode recordings and for analyzing the electrical properties of neuronal dendrites. Scientists like Coombs, Eccles, Fatt, Frank, Fuortes and others now relied heavily on cable theory to obtain functional insights of neurons and for guiding them in the design of new experiments.

Later, cable theory with its mathematical derivatives allowed ever more sophisticated neuron models to be explored by workers such as Jack, Rall, Redman, Rinzel, Idan Segev, Tuckwell, Bell, Poznanski, and Ianella.

Several important avenues of extending classical cable theory have recently seen the introduction of ionic channels and endogenous structures (Poznanski, 2010) in order to analyze the effects of different synaptic input distributions over the dendritic (see dendrite) surface of a neuron.

Deriving the cable equation

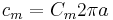

rm and cm introduced above are measured per fiber-length unit (per meter (m)). Thus rm is measured in ohm-meters (Ω·m) and cm in farads per meter (F/m). This is in contrast to Rm[Ω·m²] and Cm[F/m²], which represent the specific resistance and capacitance of the membrane measured within one unit area of membrane (m2). Thus if the radius a of the cable is known[2] and hence its circumference 2πa, rm and cm can be calculated as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

This makes sense because the bigger the circumference the larger area for charge to escape through the membrane and the smaller resistance (we divide Rm by 2πa); and the more membrane to store charge (we multiply Cm by 2πa). In a similar vein, the specific resistance Rl of the cytoplasm enables the longitudinal intracellular resistance per unit length rl[Ω·m−1] to be calculated as:

(3)

(3)

Again a reasonable equation, because the larger the cross sectional area (πa²) the larger the number of paths for the current to flow through the cytoplasm and the less resistance.

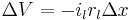

To better understand how the cable equation is derived let's first simplify our fiber from above even further and pretend it has a perfectly sealed membrane (rm is infinite) with no loss of current to the outside, and no capacitance (cm = 0). A current injected into the fiber [3] at position x = 0 would move along the inside of the fiber unchanged. Moving away from the point of injection and by using Ohm's law (V = IR) we can calculate the voltage change as:

(4)

(4)

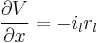

If we let Δx go towards zero and have infinitely small increments of x we can write (4) as:

(5)

(5)

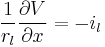

or

(6)

(6)

Bringing rm back into the picture is like making holes in a garden hose. The more holes the more water will escape to the outside, and the less water will reach a certain point of the hose. Similarly in the neuronal fiber some of the current travelling longitudinally along the inside of the fiber will escape through the membrane.

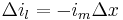

If im is the current escaping through the membrane per length unit (m), then the total current escaping along y units must be yim. Thus the change of current in the cytoplasm Δil at distance Δx from position x=0 can be written as:

(7)

(7)

or using continuous infinitesimally small increments:

(8)

(8)

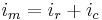

can be expressed with yet another formula, by including the capacitance. The capacitance will cause a flow of charge (current) towards the membrane on the side of the cytoplasm. This current is usually referred to as displacement current (here denoted

can be expressed with yet another formula, by including the capacitance. The capacitance will cause a flow of charge (current) towards the membrane on the side of the cytoplasm. This current is usually referred to as displacement current (here denoted  .) The flow will only take place as long as the membrane's storage capacity has not been reached.

.) The flow will only take place as long as the membrane's storage capacity has not been reached.  can then be expressed as:

can then be expressed as:

(9)

(9)

where  is the membrane's capacitance and

is the membrane's capacitance and  is the change in voltage over time. The current that passes the membrane (

is the change in voltage over time. The current that passes the membrane ( ) can be expressed as:

) can be expressed as:

(10)

(10)

and because  the following equation for

the following equation for  can be derived if no additional current is added from an electrode:

can be derived if no additional current is added from an electrode:

(11)

(11)

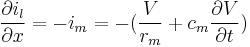

where  represents the change per unit length of the longitudinal current.

represents the change per unit length of the longitudinal current.

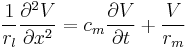

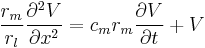

By combining equations (6) and (11) we get a first version of a cable equation:

(12)

(12)

which is a second-order partial differential equation (PDE.)

By a simple rearrangement of equation (12) (see later) it is possible to make two important terms appear, namely the length constant (sometimes referred to as the space constant) denoted  and the time constant denoted

and the time constant denoted  . The following sections focus on these terms.

. The following sections focus on these terms.

The length constant

The length constant denoted with the symbol  (lambda) is a parameter that indicates how far a current will spread along the inside of a neurite and thereby influence the voltage along that distance. The larger

(lambda) is a parameter that indicates how far a current will spread along the inside of a neurite and thereby influence the voltage along that distance. The larger  is, the farther the current will flow. The length constant can be expressed as:

is, the farther the current will flow. The length constant can be expressed as:

(13)

(13)

This formula makes sense because the larger the membrane resistance (rm) (resulting in larger  ) the more current will remain inside the cytosol to travel longitudinally along the neurite. The higher the cytosol resistance (

) the more current will remain inside the cytosol to travel longitudinally along the neurite. The higher the cytosol resistance ( ) (resulting in smaller

) (resulting in smaller  ) the harder it will be for current to travel through the cytosol and the shorter the current will be able to travel. It is possible to solve equation (12) and arrive at the following equation (which is valid in steady-state conditions, i.e. when time goes to infinity):

) the harder it will be for current to travel through the cytosol and the shorter the current will be able to travel. It is possible to solve equation (12) and arrive at the following equation (which is valid in steady-state conditions, i.e. when time goes to infinity):

(14)

(14)

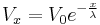

Where  is the depolarization at

is the depolarization at  (point of current injection), e is the exponential constant (approximate value 2.71828) and

(point of current injection), e is the exponential constant (approximate value 2.71828) and  is the voltage at a given distance x from x=0. When

is the voltage at a given distance x from x=0. When  then

then

(15)

(15)

and

(16)

(16)

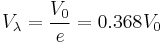

which means that when we measure  at distance

at distance  from

from  we get

we get

(17)

(17)

Thus  is always 36.8 percent of

is always 36.8 percent of  .

.

The time constant

Neuroscientists are often interested in knowing how fast the membrane potential  of a neurite is changing in response to changes in the current injected into the cytosol. The time constant

of a neurite is changing in response to changes in the current injected into the cytosol. The time constant  is an index that provides information about exactly that.

is an index that provides information about exactly that.  can be calculated as:

can be calculated as:

(18)

(18)

which seem reasonable because the larger the membrane capacitance ( ) the more current it takes to charge and discharge a patch of membrane and the longer this process will take. Thus membrane potential (voltage across the membrane) lags behind current injections. Response times vary from 1-2 milliseconds in neurons that are processing information that needs high temporal precision to 100 milliseconds or longer. A typical response time is around 20 milliseconds.

) the more current it takes to charge and discharge a patch of membrane and the longer this process will take. Thus membrane potential (voltage across the membrane) lags behind current injections. Response times vary from 1-2 milliseconds in neurons that are processing information that needs high temporal precision to 100 milliseconds or longer. A typical response time is around 20 milliseconds.

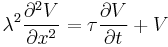

The cable equation with length and time constants

If we multiply equation (12) by  on both sides of the equal sign we get:

on both sides of the equal sign we get:

(19)

(19)

and recognize  on the left side and

on the left side and  on the right side. The cable equation can now be written in its perhaps best known form:

on the right side. The cable equation can now be written in its perhaps best known form:

(20)

(20)

See also

- Biological neuron model

- Axon

- Dendrite

- Nernst-Planck equation

- Saltatory conduction

- Bioelectrochemistry

- Membrane potential

References

- Tuckwell, H.C. (1988). Introduction to Theoretical Neurobiology. Cambridge University Press. NY.

- Poznanski, R.R., Reeke, G., Rosenberg J., Lindsay, K. & Sporns, O.(2005). Modeling in the Neurosciences. 2nd Edition. Taylor & Francis, London.

- Studies from the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, by Davis,L.,Jr. and Lorente de No. R (1947). 131: 442-496.

- The electrical constants of a crustacean nerve fibre, by Hodgkin, A.L. and Rushton, W.A.H. (1946). Proc. Roy. Soc. London. B 133: 444-479.

- Poznanski, R.R. (2010).Thermal Noise Due to Surface-Charge Effects within the Debye Layer of Endogenous Structures in Dendrites. Physical Review. E 81, 021902

Notes

- Notes:

- 1 ^ Passive here refers to the membrane resistance being voltage-independent. However recent experiments (Stuart and Sakmann 1994) with dendritic membranes shows that many of these are equipped with voltage gated ion channels thus making the resistance of the membrane voltage dependent. Consequently there has been a need to update the classical cable theory to accommodate for the fact that most dendritic membranes are not passive.

- 2 ^ Classical cable theory assumes that the fiber has a constant radius along the distance being modeled.

- 3 ^ Classical cable theory assumes that the inputs (usually injections with a micro device) are currents which can be summed linearly. This linearity does not hold for changes in synaptic membrane conductance.